We’re getting worried about Great British Railways

Nationalisation can work, but the Government isn’t doing it right

The Government is in the process of renationalising the railways. This is not, in itself, a bad idea. The best railway network in Europe, Switzerland’s, is entirely nationalised. So is South Korea’s, the second-best network in Asia after Japan. Most metro systems, including the London Underground, are publicly owned.

Who holds the shares in the railways matters less than how the system is designed. High-performing railway systems have a few common characteristics. The timetable is treated as the core product. Infrastructure spending is planned on a multi-decade basis, not chopped and changed from one year to the next. There is substantial in-house engineering capacity, which drives down the cost of building new infrastructure. The railways are not subject to meddling from politicians, and subsidies are given out in a way that prioritises competence. Timetables and fares are integrated into a single network, usually with other modes of public transport. Some of these reforms could have been attempted under the old privatised system, but many are clearly easier under nationalisation.

In one sense, the railway has already been nationalised since 2002, when the physical tracks were taken into public ownership through Network Rail. The majority of the train operating companies (TOCs) which actually run the trains are now run by the state, and the rest are expected to follow by the end of 2027. The Government is also creating a new institution, Great British Railways (GBR), which has been billed as the ‘guiding mind’ that will finally deliver a coherent railway which is able to plan for the long term.

So far, nothing resembling this vision has emerged. There is still time to turn things around. But the decisions taken so far suggest that it will not happen.

What is GBR for?

At this point, it is remarkable how much uncertainty remains about the future of the railways.

Almost as soon as the ink was dry on the Railways Act 1993, the debate about whether privatisation was a mistake began. It has consumed almost all the political oxygen about the railways for decades, which is unfortunate: even the most pro-nationalisation person wouldn’t claim that privatisation was the only thing wrong with the railways.

This narrow focus on the question of who owns the shares means that little thought has been given to what nationalisation is for. Nationalising the railways has been Labour policy for a decade. Yet the 2024 Labour manifesto was strikingly vague about what this would mean in practice. The 2017 and 2019 manifestos were more ambitious on promises of new infrastructure, but they too dodged the hard questions about how a nationalised railway would be structured or funded.

Publicly, the main argument Labour politicians have offered is that nationalisation will save the profits currently paid to private TOCs. But with profit margins of around 2–3%, that is nowhere near enough to justify a complete structural overhaul of the system. Public ownership has downsides as well as upsides, and those downsides could well be worth more than 3% of revenue.

The wider ecosystem has not filled the gap. There has been very little serious work from left-leaning think tanks on what a publicly owned railway should actually look like.1 Many have settled into cheerleading for nationalisation in the abstract, as a displacement activity for doing the hard work of thinking through governance, funding, incentives and long-term investment.

Too much ministerial micromanagement

At the moment, we don’t know very much about how GBR will actually work. But the Railways Bill currently going through Parliament looks set to give ministers sweeping powers to micromanage the railways. The Bill allows the Secretary of State to issue binding directions and guidance. GBR must implement a long-term strategy written by the Secretary of State, who also keeps broad authority to intervene in day-to-day operations. If they really wanted to, a minister could directly alter the timetable for their own convenience.

This was not the case the last time the railways were nationalised. British Rail operated at arm’s length from the Government. Although it had to go to the Treasury to get money for capital expenditure, and was dependent on subsidy, the Government usually left it to its own devices when it came to day-to-day operations. It could set its own timetables and fares, and plan the infrastructure improvements it wanted to ask the Treasury to fund.

Similarly, the Swiss railways are largely left alone. The publicly-owned Swiss railway companies make their own operational decisions; the Swiss federal and cantonal (i.e. state) governments exercise oversight by monitoring their performance, not by dictating the minutiae of the timetable.

It is right that operations be left alone. Running a railway is a highly specialised and complicated task, which requires immense amounts of process knowledge. It is not a political matter. Big infrastructure upgrades are a bit different, because they involve spending large amounts of public money, so politicians need to be the ultimate decision-makers – but day-to-day operations should not be run out of Whitehall.

The Department for Transport’s track record also does not bode well. In 2018, for instance, the Department specified a timetable for the Southwestern franchise that would have increased the number of trains running into and out of London Waterloo. This timetable would, however, have been impossible to operate, because the power supply was insufficient.

There needs to be some oversight, of course. But the best way to keep a railway accountable for its performance is through its fare revenue, which answers the question of whether it is providing a product people want to use at the right price, and through simple performance metrics like punctuality, customer satisfaction, and incident rates.

It seems unlikely that every other nationalised railway in Europe has got this wrong, and Britain has uniquely discovered a superior, more centralised, more politicised structure. A more plausible reading is that GBR is being designed as a politically controlled system that will struggle to deliver the stability, expertise and long-termism the railway needs.

GBR does in some ways resemble Transport for London, a mostly successful public sector company over which the Mayor of London has huge powers. But the Mayor has more direct accountability to the public; they are a well-known individual politician who is directly elected, and transport is by far their largest responsibility. By contrast, less than a third of the UK public have heard of Heidi Alexander. She is not directly elected, but appointed by the Prime Minister. She is already the second Transport Secretary of this Parliament, and unlikely to be the last. Plausibly voters could hold the Government as a whole responsible for the performance of GBR, but this is unlikely: trains are almost nobody’s top political priority.

We can already see the beginnings of Government meddling when it comes to fares. Under the privatised model, fares increased by inflation or faster every year. This was a decision made by the Government, but the public largely blamed the train operating companies, which gave politicians cover to make the decision. This was hardly a sensible model, but it did at least mean the railway was not starved of money.

In the recent Budget, the Chancellor announced that rail fares would be frozen. This is a problem, for several reasons. First, rail commuters are probably not the most deserving target for scarce public money, because the railway’s users skew towards affluent people with professional jobs in cities, especially London.

Second, the railways are overloaded. None of the busy lines around London has any spare capacity, give or take; nor do most of the intercity main lines. CrossCountry, which links cities outside of London, is notorious for its crowding, partly because the trains it runs often only have a couple of carriages. Freezing fares will mean more overcrowding, and starve the railways of the money they need to increase capacity. Transport for London had fare freezes between 2017 and 2020 and again in 2024, which have cumulatively led to up to £473 million in lost revenue. TfL’s business plan clearly states that they have cut capital expenditure in this period, below their ‘steady state’ requirement.2 In other words, facilities have got worse, in part because of the fare freeze.

Most importantly, GBR needs to be financially sustainable. Future governments may not be as ideologically supportive of rail transport as Labour, or might face even tighter budgetary constraints. GBR needs to reduce its reliance on subsidy over time, not push it further up.

The fare freeze is a measure which might win the Government some political support in the short term, but is against the best interests of the railway long term. We may well see more of this kind of thing if ministers are given the power to manage GBR: an obvious example is slowing down long-distance trains by adding stops at small stations after a spirited campaign by the local MP.

Infrastructure costs remain high

Britain’s railway network is a series of pinch points linked by bottlenecks. It desperately needs money spent on it to cope with the vast numbers of people who want to use it: more tracks, bigger stations, resignalling, electrification, and redesigned junctions. This is plausibly the single biggest problem facing the railways, but here the Government has been silent.

Part of the reason the railway has been starved of investment is that railway infrastructure is more expensive in Britain than in almost any other country. Most notoriously, HS2 is the most expensive high-speed line the world has ever built. It costs over 50% more per kilometre than the world’s fastest train, the Chūō Shinkansen in Japan. This is going to be the world’s fastest train, a maglev which will run at 500 km/h, 100 km/h more than HS2’s design speed. The track will mostly be dug in a long tunnel between Tokyo and Nagoya under the Japanese Alps.

The problem is not limited to high-speed infrastructure. The problem of high construction costs dogs the whole of the railway industry.

Consider electrification. An electric railway is a better railway, however you define ‘better’: electric trains are faster, cleaner, greener, cheaper to run, and more reliable. Britain, however, is a long way behind other European countries on electrification:

A big part of the reason is that British rail electrification is around three times as expensive as in Germany. One of the key drivers of those higher costs is Britain’s habit of running electrification as a series of one-off projects. Every time a programme finishes, the workforce disperses or goes overseas; every time a new scheme starts, the system has to re-create capacity from scratch.

If you worked on the last major electrification burst in 2018–19, there was no steady pipeline to move onto. The choice was to leave the industry or leave the country.

Germany, by contrast, has been electrifying around 200 km of railway per year since the 1960s, with the benefits of continuity in skills, procurement and project management. British Rail, for all its flaws, took this approach. As a result, the cost in the 1980s to electrify the East Coast Main Line between London, Edinburgh, Newcastle and Leeds was seven times less than the cost of electrifying the Great Western Main Line between London, Bristol and Cardiff in the 2010s.

The Government does not have a plan to bring costs down. As a result, we are back in the ‘famine’ stage of ‘feast and famine’. One key electrification project is the Midland Main Line between London, Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield. It is currently electrified from London to just south of Leicester. Everything heading north relies on diesel; Sheffield is the largest city in Europe without a single electrified railway.

The Midland Main Line should have been electrified decades ago. Transport Secretary Heidi Alexander’s decision to ‘pause’ or cancel its electrification is therefore extremely worrying. The Financial Times has reported that around £70 million already spent will now be wasted. When the line eventually does get electrified, costs will be even higher, because the remaining workforce and process knowledge from previous electrification projects will have dissipated. Costs were already projected at around £1.3 billion. A stop-start approach will push them higher still.

What is most revealing is the way this decision was made: as an isolated announcement, not part of a considered, multi-decade strategy for electrification across the network. That strongly suggests that the much-hyped ‘guiding mind’ of GBR is likely to be just as ad hoc as the system it replaces. And if that is true, it will not bring infrastructure costs down in the long run.

Taking it all together

Individually, each of these decisions might be defensible. A cautious Opposition may lack the resources to design a detailed rail reform blueprint before taking office. Ministers may want time to think through decades-long decisions before locking in a national rail strategy. A fares freeze might be seen as a way of buying goodwill from passengers at the start of nationalisation. The Government might be nervous about signing a large, open-ended cheque for Midland Main Line electrification until it believes costs can be better controlled.

But taken together, the choices form an incoherent whole. You cannot credibly claim there is no money to electrify the main lines to some of Britain’s largest cities, infrastructure that is standard across much of Europe, while simultaneously spending around £775 million on a fare freeze.

You cannot say you want a stable, long-term, expert-led ‘guiding mind’ for the railway and then design a structure in which ministers can fiddle around with the timetable and operational decisions.

You cannot talk about driving down rail infrastructure costs while continuing the same stop-start pattern that keeps those costs high.

What we should be aiming for

We have mentioned the Swiss system several times, for good reason: it is what we should be aiming for. The political argument in favour of nationalisation has been won. The details should learn from other successful systems, in particular the triumphant Swiss network. On average, each Swiss person travels almost 2,500 km by rail every year, the highest in Europe and nearly three times the British figure of 879 km.

One of the most striking features of Switzerland’s network is the degree of local control. Switzerland is famously a hyper-decentralised country, which is reflected in the structure of its railway industry. There are dozens of different publicly-owned railway companies in Switzerland, most of them owned by the cantons (i.e. states). They are able to tailor their offering to the needs of the region: it is as if Cornwall owned and funded the network of branch lines connecting towns like Newquay and St Ives with the rest of the network.

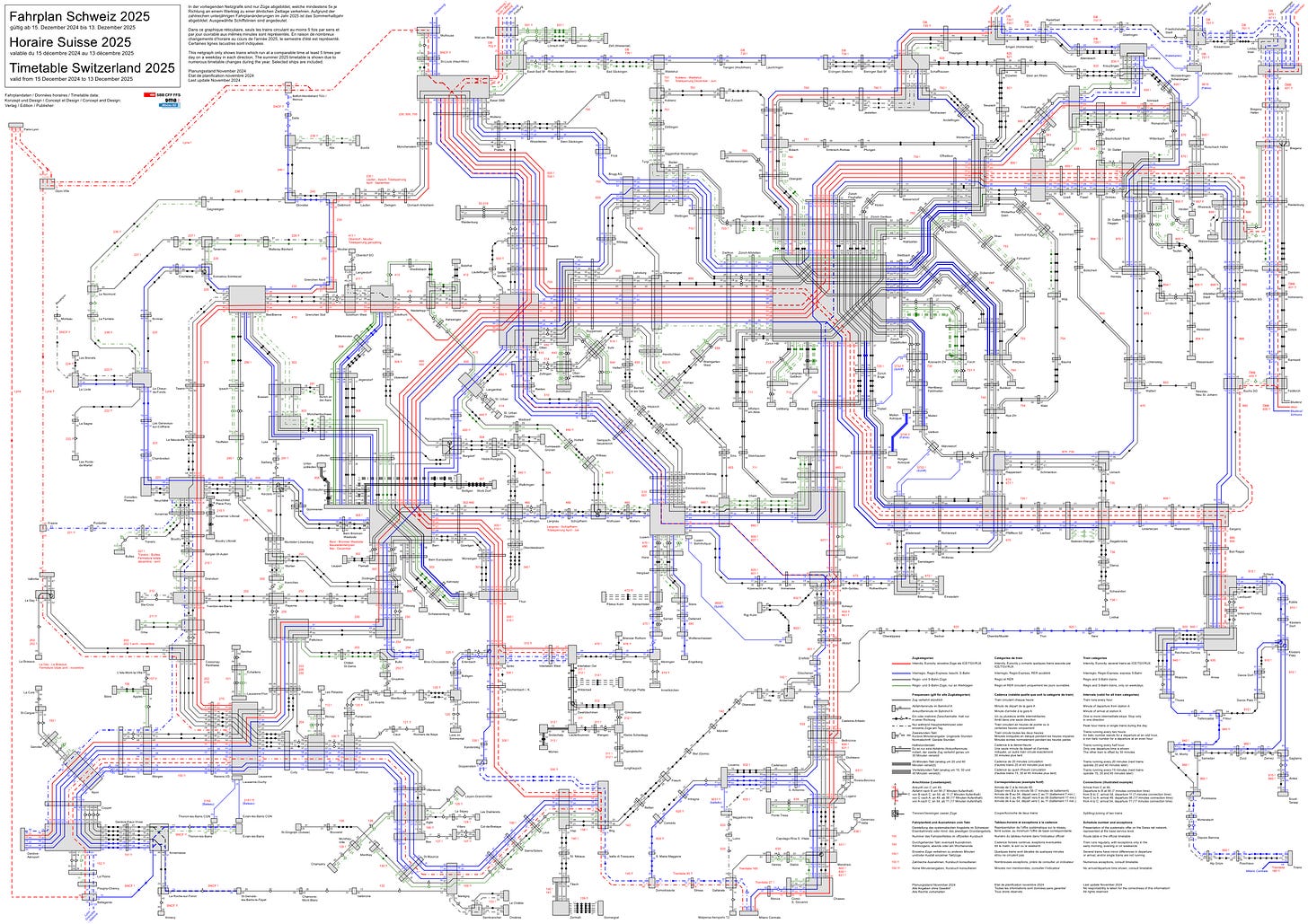

At the same time, these companies are all integrated into a genuinely national network: Switzerland does have a ‘guiding mind’, while avoiding the pitfalls of overcentralisation. Around each city the fares of different operators are co-ordinated into a simple zonal system, and the Swiss timetable is designed so that trains connect with one another, even when they are run by different operators. You can see the whole of the Swiss timetable on one diagram:

This local control is paired with local funding. The cantons are able to pay for investments within the canton, with funds matched by the federal government. Subsidy for loss-making services is done according to the ‘customer principle’: the cantons ‘buy’ services from the railways, which means there is a direct connection between how much money they want to spend on transport and the quality of service they get.

Not everything is controlled locally: the long-distance network, for instance, is of national importance. Here, however, Swiss Federal Railways is able to plan infrastructure upgrades autonomously, and the close integration between track and train means that the Swiss are able first to design a timetable, and then design the infrastructure to operate it, a reversal of how things are done in Britain.

Finally, there is a pipeline of infrastructure upgrades, and a dedicated fund which the railways can use for this investment. The fund gets 0.1% of VAT revenue, along with ⅔ of the tax on heavy lorries, 9% of the tax on fuel, and contributions from the federal and cantonal budgets. The railways have certainty over their investment pipeline, which helps reduce construction costs to something close to the European average.

Switzerland has small cities and the country is full of mountains. Our cities are much bigger than Zürich or Geneva, and our terrain is fairly flat. Given these natural advantages, with the right policy decisions we could end up with a railway network that is even better than the best in Europe.

It isn’t all bad

There have been some moves towards greater regional control. The Department for Transport is creating a formal rail “Right to Request” process, allowing any established Mayoral Combined Authority to ask for control over specific rail services, stations or infrastructure in its region. In Greater Manchester significant extra control will bring 96 stations and 8 rail routes under the Bee Network. While Manchester is ahead of others, it is plausible that within a few years many large city regions will have transport powers that are routine across Europe but were effectively illegal in Britain until very recently.

The catch is that this is only a “right to request”, not a guaranteed right to receive. The real test will be how the Government responds when mayors with serious, credible plans seek much greater control over rail in their areas.

Another announcement that appears to move in the right direction is the emerging approach to schemes like the Thamesmead DLR extension. The details are still fuzzy, but the broad direction seems to be this: if London wants more transport infrastructure, London will increasingly be expected to pay more of the bill itself, rather than relying on general taxpayer support from the rest of Britain.

That is, in principle, exactly as it should be. London is affluent, and its transport investments generate huge economic benefits. It is very good for the national economy for London to get lots of new transport investment. But London should pay for every penny of it.

There is no indication that there will be a general power for city regions to fund their own transport infrastructure. Andy Burnham will not have the ability to fund a Manchester Crossrail from Manchester money, as he would in Switzerland or France or Germany or Spain.

The report card

The Government’s rail record so far is mixed. On mayoral powers and, to a lesser extent, London’s funding more of its own projects, the direction is encouraging. On GBR’s structure, fares policy and infrastructure decisions, the choices are far more troubling.

A striking pattern emerges: the decisions that look promising tend to be those that do not heavily involve GBR. The ones that look short-termist, incoherent or costly are those that do.

For this Government to have a genuinely positive impact on Britain’s railways, it will need to change how GBR is conceived and run, quickly.

The forthcoming National Rail Strategy is the natural moment to do this. It will set out what the Secretary of State intends to do with the immense powers the Railways Bill provides. If the Government uses that opportunity to pull back from micromanagement, commit to a long-term, continuous electrification and investment pipeline (even if the annual investment is small), align fares policy with capacity and long-term financial sustainability, and give cities more powers to run their own trains and build their own infrastructure, then GBR could still evolve into the kind of stable, expert-led, long-term railway system Britain needs.

If not, there is a real risk that Great British Railways will end up as a more centralised, more politicised version of a system that already doesn’t work, and that would be an opportunity wasted on a historic scale.

Thank you to Thomas Ableman for his help with this work.

I (Michael) could not find anything longer than a page put out by any of the Institute for Public Policy Research, Commonwealth, New Economics Foundation, CLASS or Labour Together. If there are any I have missed, let me know.

TfL Business Plan 2023: “Having constrained our investment in capital renewals to between £400m and £600m per year for the last five years, against an estimated steady state requirement of around £1bn per year, this Business Plan sets out a renewals investment plan that builds up to a sustained level of around £850m.”